|

There are large files and images on this page please wait while loading

| Extracts from: "The Story of Haversham" by Rev. Samuel Hilton, M.A. Rector of Haversham

The Romans.

That Roman coins should have been found here is not surprising, when one notes its situation near to the famous Watling Street, up and down which the Roman legions tramped for 400 years. The pity of it is that such coins as have been discovered, have disappeared from the district, and are not even to be found in public museums. Fortunately, one of them at least has been officially recorded, viz.: a brass of the reign of Marcus Aurelius, who was emperor from 161 to 180. Sixty-seven years ago there was exhibited to the London Society of Antiquarians a steel-yard weight, in the form of a woman’s head, which had been ploughed up in the parish. This weight is of special interest, as it is one of the few traces of any local industry during the Roman period, which have been discovered. Over half a century ago many coins obtained from farm-workers, who ploughed them up in the neighbourhood of the “Freeboard” at the N.E. border of the parish. At this place there are obvious traces of an ancient earth-work, commanding a sort of glacis. The Anglo-Saxons.

The Danes.

Princess Ælfgifu. There lived in the 10th century a lady of royal decent named Aelfgifu, or Elgiva, of whose identity there is some uncertainty. It is indeed quite likely that she was the lady whom the young King Eadwig married, and whose marriage was annulled by Archbishop Oda on account of close kinship, probably first or second cousin. She certainly was a kinswoman of King Edgar “the peaceful,” who succeeded his brother Eadwig in 959. Her brother Aethelweard was an Ealdorman, one of the powerful men of the kingdom, and a great-great-grandson of King Ethelred, the elder brother of King Alfred.

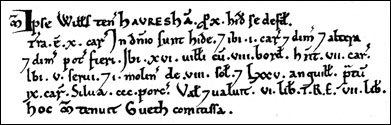

DOOMESDAY BOOK, 1086, A.D.

Translation Manor. William himself holds Havresham: it is assessed at X. hides. There is land for X. ploughs. In the demesne are … hides, and on it are I. and a half ploughs, and another and a half there could be. There XVI. villains with VIII. bordars have VII. ploughs. There are V. serfs and I. mill worth VIII. Shillings and LXXV. Ells Meadow (for) IX. Plough-teams. Woodland. CCC. Swine. It is valued and was valued at VI. Pounds. In the time of King Edward, VII. Pounds This Manor Countess Gueth held. This most interesting document has several things to say about Haversham of 1086. First of all, it will be noticed that the Norman-French enumerator confused the name of the place with the French word Havre, which means a haven. One would like to think of the village as suggesting to him a peaceful haven of rest. The final consonant in such as Haversham and cum is indicated by a line over the previous letter. The extent of the place is estimated at 10 hides, which is roughly speaking 1,200 acres (Its present acreage is given at 1,634 [in 1937]). There was considerable arable or plough-lands, a plough-land (“car” from the Latin carruca) being as much land as a team of oxen could plough annually, and eight oxen being reckoned to each plough. A mill is mentioned, part of the rental of which was payable in ells, -caught in the mill pond presumably. It is thought that possibly the meaning of the expression “Woodland: 300 pigs:” is that the wood was sufficiently large to maintain so many swine. There was a fair population of 24 households of villains and bordars, besides the 5 families of serfs, who worked the Manor land. This would represent a total population of between 100 and 150. It is estimated that a total of the 300,00 families in England at this time, one third were villains, who held small portions of land at the will of their lord, more or less as small-holders, and who were bound to give whatever service he demanded. Of bordars there were 90,000, who were of lesser status than the villains. In Saxon times many of these had been free-holders, but they had sunk into subjection to the Norman lords as cottagers. At Haversham these two classes of 24 households held, under William Peverel, as much land as 7 ploughs could cultivate. Of serfs there were 25,000 families in the land. They were the labourers, without property or holdings, and were chiefly connected with the private property of the Manor. At Haversham they cultivated 1½ plough-lands, and another 1½ they left uncultivated. Countess Gueth. It is stated in the Domesday Book that the Manor of Haversham was held in Saxon times by “Gueth comitissa.” There has, however, been some difference of opinion as to the identity of this lady. The earlier histories of the parish have claimed the authority of a 12th century librarian of Malmesbury Abbey for the statement that she was the sister of Sweyn, king of Denmark, and the widow of Godwin, Earl of Wessex. If that were so, her son was none other than the famous Harold, the lawful king of England, whom the ambitious William Duke of Normandy, overthrew at Senlac near Hastings in 1066; and her daughter was Eadgyth (or Edith) who married King Edward, called “the Confessor.” The trouble is, that there were three or four other ladies of this name at the time, and the name is variously spelt. Gueth is the Norman spelling of Gythe, which is also found as Gethe, Githe, or Latinised as Gytha, Githa, &c., and Charles Kingsley, in “Hereward the Wake,” spells it Gyda. The latest authorities on the subject are definitely of the opinion that the Saxon holder of Haversham must be the same person as Gethe, wife of Earl Ralph of Hereford, who is mentioned in the previous entry in Domesday Book, as owning Edestocha (Adstock): “this manor Gethe wife of Ralph held, and could sell.” We know little of this countess, except that her name is either English of Danish, that she had a son who was named Harold, and that she possessed considerable property in the counties of Northampton and Buckingham. As the widow of Earl Godwin was also Gytha (the same name as Gueth), it is easy to see how the confusion has arisen between the two families. Professor Freeman thinks that the similarity of the names of both mothers and both sons may point to some sort of connection between the two houses of Wessex and Hereford. Of Countess Gueth’s husband, Ralph Earl of Hereford much more is known. He is distinguished from several of his namesakes of the period by the impolite epithet of “the Timid,” his military qualities not being og a very high order. On his mother’s side he was great-grandson of King Edgar, to whom Haversham had been bequeathed a century before. Moreover, his mother was a sister of both King Edmund Ironside and King Edward the Confessor. He seemed in fact to be very near to the succession of the English throne, and possibly King Edward would have named him as his successor, had he not died in Dec., 1059. He was not a popular prince, for in addition to his “timid” reputation, he was of foreign birth on his father’s side, and normally spoke the French language. It would seem that the Countess Gueth did not survive Earl Ralph very long. Their young son Harold was in the wardship of Lady Eadgyth, the sister of King Harold, in 1066, and was never allowed by the Conqueror to succeed to the estates and dignities of his parents. William Peverel. The Manor of Haversham, along with much, if not all of the property of Countess Gueth, was bestowed by the Conqueror upon a powerful Norman noble of unknown antecedents named William Peverel. A legend, which has not the least shred of evidence, used to be current about him that he was the illegitimate son of the Conqueror. Professor Freeman says of this story that it was “an utterly uncertified and almost impossible scandal.” Peverel certainly was in high favour with the Conqueror, who bestowed upon in extensive properties in the Midland Counties of Northampton, Nottingham, Leicester, Derby, and nine manors in the county of Buckingham, besides a castle in the Peak Forest. He was also one of the important barons of the time. He is best known as being the ancestor of “The Peverel of the Peak,” immortalised by Sir Walter Scott. The Domesday Book gives the information that at that date (1086) he did not have a tenant in charge of his Haversham estate, but that he retained it for his personal use and occupation “in demesne.” The chief respect in which this Norman noble left his mark on the pages of history was not because of his military exploits, but by the fact that he found two religious houses. The first one was established in the western suburbs of Northampton about the year 1104, for the canons of the order of St. Augustine, and was dedicated to St. James the Apostle. This abbey he founded “for the salvation of his own soul, and of the souls of his father and mother, and of all the faithful departed.” The abbey has long since disappeared, but the district is still known as “St. James.” The other house he founded was the priory at Lenton, near Nottingham, somewhere between the years 1109 and 1113. This house, dedicated to the Holy Trinity, he founded “out of love of divine worship and for the good of the souls of his lord King William, and also for the health of the soul of the present lord King Henry and Queen Matilda.” Further, Peverel required his man “for the cure of their souls” to continue “two parts of all the tithes of their demesnes of all things which could be tithed,” among these men is mentioned “Walterus Flammeth in Hauresham.” Evidently by this date Peverel had appointed a tenant to be in charge of his Manor at Haversham. According to the register of the Priory of St. James, he died in 1113, his son William having died three years before him. William Peverel the younger. His grandson, also named William, was an outstanding character during the troublous reign of King Stephen. He warmly espoused the cause of Stephen of Blois in opposition to Matilda, the daughter of Henry I., a step which led eventually to his undoing. At the Great Council held at Oxford in 1135 he was one of the temporal lords who attended King Stephen. In 1138, when David of Scotland invaded England, Peverel was one of the chief commanders who won the victory over the Scots at Northallerton, called the battle of the Standard. In the struggle with the forces of Matilda he was not so fortunate, as he was taken prisoner, along with King Stephen, at Lincoln in 1141. Matilda’s forces also took his castle at Nottingham, but Peverel’s men recaptured it and expelled from the town all the supporters of Matilda. When Stephen died in 1154 and Matilda’s son Henry succeeded to the throne, all the vast estates of Peverel were forfeited, because of his support of the late king. Indeed, two years before Henry came to the throne, the confiscation of the Peverel property had been contemplated by him, for he had promised the whole of it to Ranulph, Earl of Chester, unless Wm. Peverel “could clear himself in my court of his crime and treason.” When the Earl of Chester died of poisoning soon after this promise had been made to him, it was generally assumed that Peverel was the person responsible for the offence. His position therefore was quite hopeless when Henry II. came to the throne, and so he took refuge in a monastery – probably Lenton, where he assumed the tonsure and habit of a monk. He was not to find peace here for long. When he heard the year following that King Henry was about to journey through Nottingham, he fled from this monastery, and was never heard of again; probably he concealed himself in some other monastery. His castle and all his possessions were therefore left entirely at the new king’s disposal. With this unhappy incident, the connection between Haversham and the Perverels came to an end, except that in the official references to the manor throughout the next four centuries it is spoken of as being “of the honour of Peverel.” THE DE HAVERSHAM FAMILY, 1174 to 1289

Arms of “Nicol. De Haversham” (Hen: III Roll) Azure, crusilly, and a fess argent. The old records are silent as to the manner in which the de Haversham family came to be in possession. No hint is given as to whether they were in any degree connected with the Peverels, or descendants of the Walter Flammeth who gave part of the tithes to Lenton Priory early in the 12th century. Possibly they were favourites of Henry II, upon whom the King bestowed the Manor after the disappearance of William Peverel. They suddenly appear upon the scene about the year 1174, apparently being in possession, and as already known by the name of the place, which fact would suggest that they had been associated with Haversham for some time past. They are first made known to us by somewhat casual references to two members of the family in the Great Rolls in the Exchequer called the “Pipe Rolls,” containing the accompts of the King’s revenue. The first reference is an obscure one to a Robert de Hauerisham in the 21st year of Henry II, 1174-5 A.D. It appears that he defaulted to make an appearance at his neighbour’s court in a matter of the testing of coins by melting them down. Whatever the affair could have been, it was settled by the payment of one mark into the Treasury. In the same year the name of “Nicol: de Hauersham” appears in these Rolls. His daughter had been given by King Henry II to William de Bello in marriage, and so Nicholas had to pay 20 marks into the Treasury. Again two years later, this same Nicholas is merely mentioned as paying 10 marks into the Treasury on account of some debt, which was settled. There are no means of ascertaining the relationship of Robert and Nicholas, the first members of the de Haversham family to be mentioned in the old records; possibly they were father and son. Whatever their origin they took their name from the place, and for nearly 500 years their descendants held the Manor with creditable distinction, “of the King in chief by service of one knight’s fee as of the honour of Peverel. The description of the Manor as being “Of the honour of Peverel” occurs regularly until 1525. It would seem that the King did not at first confer Haversham upon them in its entirety, for in 1190, the 2nd year of Richard II, Hugh de Haversham had to pay a sum of money. (30) marks so that an investigation might be made into the question, whether the wood of Haversham belonged to his estate or to the king’s demesne. Again in 1199, when John came to the throne, Hugh was called upon to pay a further 30 marks to obtain the King’s confirmation of his charter relating to his woodland. The King’s accounts show that Hugh actually paid only 20 marks at the time and that 10 marks remained owing (“et debet x.m.”). Even this did not include game rights as yet, for it was not until 1233 that free grant of warren in the manor and fields of Haversham was given to Hugh’s son Nicholas and his heirs. By 1242 the title of the family to the possession of the estate was considered to be of old standing, as is shown by a reference contained in the Book of Fees for this County: “Comitatus Buk.’ Haversham. De veteri. Nicholaus de Haveresham cum suis tenentibus tenet unum feodum de honore Peverel.” The Case of Hugh and Benedict. King John, who succeeded his crusading brother Richard in 1199, is chiefly known to history because of the Great Charter which he confirmed and sealed at Runnymede in 1215. The special interest of Haversham in him is not only that in the first year of his reign he confirmed the Charter of Hugh de Haversham in possession of the woodland for a consideration but that in the 9th year of his reign, a case was tried at Marlborough between Hugh and Benedict (? his brother or uncle) at which the King himself was present .The purpose of the case was to obtain a decision concerning rights of pasturage in certain lands and fortunately it has been recorded at length. A translation of it is given below.

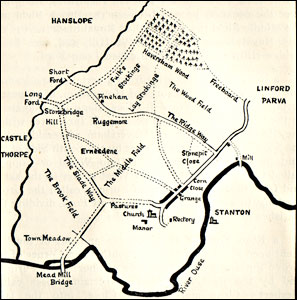

A translation of “Pedes Finium,” Hunter, page 242 THE FINAL SETTLEMENT IN 1207 A.D. This is the final agreement made in the King’s court at Merleb’ge (Marlborough) on the 15th day after the feast of St. Martin, in the 9th year of the reign of King John, in the presence of the Lord King himself (and others named) …. Between Benedict de Haveresham petitioning and Hugh de Haveresham tenant, concerning 42 acres of land with appurtenances in Haveresham. One thing was agreed between them in the aforesaid court namely, that the aforesaid Benedict recognised the whole forementioned land with appurtenances to be lawfully Hugh’s own. And on account of this recognition and fine and agreement, the same Hugh gave and conceded to the same Benedict twelve acres of woodland, measured by the King’s perch, in the wood which is called Ernesden’ towards the west, and six acres of land of the same vill, measured by the legal perch, namely in Lauedistoking, to have to hold to himself and his heirs, of Hugh himself and his heirs alike, with a fourth part of a knight’s fee, which formerly he held of him in the same vill. And on account of this gift and concession, the same Benedict conceded to the men of Hugh de Haveresham himself along with his men of the same vill. That they should have the right to pasture cattle in Benedict’s own grazing land, which is called Ruggemore. And, for himself and his heirs, he remitted and quit-claimed to the same Hugh all right to pasture cattle, which he had or claimed to have in the park of Hugh de Haveresham himself. Ernesdene: the name is drived from the Old English words “erne,” an eagle, and “dene,” a wooded valley. It is probably in the neighbourhood of the fields called Arden Well. Lauedistoking: that is, a clearing surrounded by stakes. It is the present Lay Stockings, alongside the wood to the north of the Ridgeway. Ruggemore: from the Old English words “rugge,” a ridge, and “more,” a heath or waste land. It is the high ground which the Ridgeway crosses, and is probably somewhere about the field now called Rowditch. The Ridgeway and Lay Stockings rise to a height of 323 feet above sea level, or about 120 feet above the village. Judicial Enquiry of 1273. Some most interesting pieces of information of this period have been preserved in two official enquiries made a this time. As was customary on the death of a landowner, an enquiry or inquisition was made on the nature and extent of the property lately held by Nicholas de Haversham, so that a decision might be made as to his legal heir, and a dower awarded to his widow. To be precise, this enquiry was held on “the Saturday after St. Gregory in the 2nd year of Edward I.” It was found that his estate consisted of Compton Manor and other lands in Wilts., property in Southampton, Claybrok in Leicester, in addition to Haversham with the advowson of its Church, and that his daughter Maud aged ½ year was his next heir. The total value of all lands was given at £112 6s 8½d., of which Haversham alone accounted for £59 8s 3½d., “and so to the Lady (i.e., Joan his widow) ought to be dowered of £37 8s 10¾d., that is one third of the value. The Rolls of the Hundreds, 1278 In the latter half of the 13th century there were also kept records, called “The Rolls of the Hundreds,” which are a most profitable source of information. They contain several references of interest to the story of Haversham, and especially are they valuable for the detailed report given of the estate here, with a full list of the 46 tenants and the amounts of the rentals which they paid in the year 1278. ["Rotuli Hundredorum, vol II., 346. 7 Edward I"Haversham was then included in the Hundred of Bonestowe, as it was in the days of the "Domesday Book". The 12 jurors, who were named, began by declaring that “Maud, daughter of Nicholas de Haversham, held the whole manor of Haversham, with the advowson (cum advocatione) the Church, of the Lord King in Chief by service of one knight’s fee, and is of the honour of Peverel.” According to these returns, the average size of a holding was 9 acres, whatever area that might have been in those days. No less than 38 holdings out of the total of 46 were of this size, and the rental that was paid for such a holding was 13/4, along with other services as a rule. Even after the lapse of 600 years the names of some of the tenants have a familiar ring about them: such as Ralph Parker, Henry Temple, Adam Wyteing, Richard Bayle, John le Paumer, Henry King, John Baldwyne and Simon Baldwyne. The smaller manor, which in 1207 was in the hands of Benedict de Haversham was now held by “Lord John de Haversham,” as a sub-tenant of Baldwin de Bello Aneto (or Belony), and he paid for it the nominal rental of a pound of cumin annually. A John de Haversham, presumably the same person, is mentioned elsewhere in the same year as holding lands in Nerer Orton, Com’ Oxon. A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF “HAVERSHAM” PARISH IN 1278, ACCORDING TO THE ROLLS OF THE HUNDREDS. A translation of “Rotuli Hundredorum,” vol. II, p. 346 These are the names of the 12 jurors …. Who say that Matilda, daughter of Nichols de Haversam, holds the whole Manor of Haversam entire, with the advowson of the Church, of the Lord King in chief, by service of one knight’s fee, and is of the honour of Peverel, and pays a rent of 10 shillings per annum to the Lord King, and she has here in demesne 620 acres, of which 234 acres is land held by villein-tenure. Of these Robert al Fispond holds 9 acres of the said villenage, and his service is worth per annum, in works as well as in other obligations and aids 13/4, and he gives “merchet” for his own flesh and blood. (25 other tenants named) each of whom holds 9 acres by the same service as the said Robert ad Fispond. Also John del Aubel holds 9 acres of land freely for his lifetime, and pays a rent to the said Matilda of 13/4 per annum. (5 other tenants named) hold 9 acres of the same lady by service. Also Walter Bending holds 5 acres from the same lady and pays 6/8 per annum. Also Galfr’ Molindinar’ holds 18 acres with the mill from the same lady and pays 113/4 per annum. Also the said Matilda Lady of the Manor, has here free fishing in the water which is called Use. Also the said Church of Haversam is endowed with 72 acres. Lord de Haversam holds 90 acres from Baldewin de Bello Aneto and the said Baldwyn holds it from the said Matilda, the tenant-in-chief, and pays a rent of one pound of cumin per annum and gives as scutage a fourth part of a knight’s fee. 54 acres of this land is in villein-tenure, of which Henry King holds 9 acres of land, and he pays per annum in works and aids to the value of 13/4, and he gives “merchet” for his flesh and blood. (5 other Tenants named) each of whom holds in that place 9 acres of land by the same sort of service as the said Henry King performs. Also Robert Faber holds one messuage and half an acre of land from the said Lord John freely, and pays him 4/- per annum. Also Henry Wynegos holds from the said John 18 acres freely, and pays him 1d. per annum. Also Simon le Rus holds from the said John 16 acres of land freely, and pays annually 4/- per annum, with small (? plots) freely to his tenants. Also Thomas de Britannia (i.e., Brittany) holds 24 acres of land freely, and pays annually 4d. and one pound of cumin to the tenant-in-chief, and 1d. to Lord John de Haversam. Also (he pays) 0/- to God and to the Church of the Blessed Mary of Haversam for the maintenance of lights (i.e., candles). Also John Molindinar’ holds from the Thomas 6 acres freely, and pays him annually 9/1, and (pays) 2/- to God and to the Church. Also John del Aubel holds 6 acres freely from the said Thomas and pays him annually 1d., and (he pays) 2/- to God and to the Church for the maintenance of lights. Notes: An acres was originally an open, ploughed or sowed field, excluding woodland and waste land, and it was not a legally defined measure of surface area until 1357. The actual area of the above “ccccc & xx acres” is therefore doubtful. “Merchet”: i.e., pays a fine to the lord for liberty to give a daughter in marriage. Who was Thomas de Britannia? It would seem that he was probably connected with Lavendon Abbey. There was a John de Britannia who was Earl of Richmond at this time, and Thomas may have been a member of the family. The word Ouse, or Use, is derived from the Cymric wysg, meaning water. The Dove-cote and Fishpond.

The first mention of the ancient dove-cote or columbarium is discovered at this time. The Inquisition of 1273 declared that the value of the manor house, along with the dove-cote, grange, garden, and vineyard was assessed at 30/- per annum. On that calculation, an annual payment of 9/- to the Church was by no means a negligible sum. The dove-cote was mentioned again in 1335, when Hawise, the widow of Sir William de la Plaunche, was granted a right to one-third of it. It was restored by Maurice Thompson in 1665. Elsewhere it has been placed on record that complaints were made in 1274 of the conduct of the representatives of the royal Custodian, during the minority of Maud de Haversham. The bailiff and under-bailiff of the King’s escheator (Richard de Clifford and Adams by name) were accused of selling the timber of the wood in the neighbourhood of Haversham (boscum apud Haveresham to the value of 21/3, and they were further accused of destroying the fishpond (vivarium). About the same time a complaint was made that the sub-escheator in Con’ Wyltes’, Walter Luvel by name, had felled 9 oak trees in the park at Compton, while the property of the late Nicholas de Haversham was in the King’s hands. THE DE LA PLAUNCHE FAMILY, 1289-c.1389.

Arms: Argent billety and a lion sable. Maud de Haversham was only 16 years old when the wardship of the Queen came to an end. She became married to Sir James de la Plaunche, and the following order was issued to Master Henry de Bray, the escheator this side Trent in 1289:- “Order to deliver to John [this is an error for James] de la Plaunche and Maud de Haversham his wife, all the lands whereof Nicholas here father, tenant in chide, was seised at his death, to be held until the King’s arrival in England, so that there may be done what the King shall cause to be ordained by his council, as the King learns … that Matilda is of full age.” Her husband was not to live more than 16 years afterwards, and of him two things only are told. He exercised the right of patronage to the rectory on the death of Master Angelus in 1291, and appointed William de Ledcomb, of whose subsequent troubles on the death of his patron we shall soon hear.

Little Linford, or Lynford Pava. One of the few recorded touches with the neighbouring village happened in the days of Sir John de Olney. On behalf of his wife, Lady Maud, he lodged a claim in 1314 to the manor of Little Linford, stating that her great-grandfather, Hugh de Haversham, had held it in the days of King John. The claim does not appear to have been successful; but in 1325, at the inquisition held after the death of John de Olneye, it was found that besides holding Haversham and Compton Chamberlayne (jointly with his wife Maud) he held some lands in Hardmead, and the manor of Lynford Parva. The latter had come to him on the death of Thomas de Hautville, “who had mortgaged the same to the said John for a certain sum of money which he ought to have paid at the feast of St. Michael last, before which day the said John died.” However, the overlord John de Somery interfered, and seized Little Linford for himself, so that neither the de la Plaunche nor the de Olney family was able to retain it. Lady Maud survived her second husband by four years, leaving a third child, John de Olney, besides William and Joan de la Plaunche. More will be heard later of the descendants of these three children. The Inquisitions of 1335 and 1347. Nothing is known of the influence of either the son or the grandson of Lady Maud, both of whom were named Sir William de la Plaunche. They both died in early manhood, the former being 34 years old and the latter only 21. These were the days of almost continuous warfare with Scotland and France. The inquisitions held at their deaths have placed on record a few points of interest. The widow of the first Sir William, Hawis by name, having given her oath not to marry again without the King’s licence, had in 1335 a dower assigned to her of portions of the manor house, namely: “The great chamber with the chapel at the head of it beyond the door of the hall, the maids’ chamber with the gallery (Oriola) leading from the hall to the great chamber, the said door into the hall to be shut at the will of Hawis; also the painted chamber next to the great chamber, with a wardrobe; a dairy house with the space between the dairy and the door into the great kitchen, which door could be shut at Hawis’ pleasure; the new stable with the house called the cart-house, a grange called Kulnhouse, a third part of the dove-cote, &c.” Seven years later, a royal mandate was issued “for livery to Hawisia, late the wife of William de la Plaunk, tenant-in-chief, out of the knight’s fees held by Richard de Belauney in Haversham, and extended at £4 yearly, which the King has assigned to her dower.” The advowson of the Church of Bereford St. Martin, Co. Wilts., was also assigned to her. On the death of the second Sir William de la Plaunche in 1347, a writ was issued to assign to his widow Elizabeth (a daughter of Sir Roger Hillary, Chief Justice of Common Pleas) “her reasonable dower of the lands, &c., of the said William,” which was as follows:- “A third part of two parts of the Manor, including a messuage, a chamber beyond the gate with solar [a loft or upper chamber] and houses, a small close, … a third part of the grange towards the Church, and of the adjacent barton, [an outhouse and yard] the middle stable, with a small herbarium opposite the door of the hall, and a third part of the orchard with the fishpond there &c.” This Sir William left in 1347 two children, Katherine aged 5 years and Joan aged 4, and after his death a third daughter, Elizabeth was born. The second girl, Joan, died in infancy, and the other two inherited; first Katherine on her marriage with William de Birmingham, “son of Fulk de Bermyngham, knt.” And secondly Elizabeth her sister had died leaving no children. Elizabeth also married a son of Fulk de Bermygham, named John. The de Havershams. It must not be supposed that the name of the old family had already died out. Certain members of it were very much alive at this period, only they were not in the direct line of succession. The Patent Rolls of Edward II and Edward III mention them four times. They record that the Chaplain was John de Haversham and that in 1325 he made a generous gift to Lavendon Abbey. Possibly he was a son of the John de Haversham who held the manor of Belauney in 1278. In 1345 Brothers Stephen de Haversham and Roger de Bermyngham were fellow canons of the sub-prior and convent of the conventual Church of Kenilleworth. Another de Haversham, Robert by name, was appointed with others to arrest all persons prosecuting appeals in derogation of the judgement of the Court of Common Bench. This was in 1348; and the next year Master Richard de Haversham, who was the treasurer of the Church of Llandaff, adjudicated in a matter of variance concerning the patronage of a Church. The same Rolls of Edward III in sanctioning an exchange of benefices throw an interesting sidelight on the condition of the times. This is the record in 1351:- “Presentation of Roger de Aston, parson of the Church of Haversham, in the dioc. of Lincoln, to the Church of Fenny Drayton, in the same diocese, in the King’s gift by reason of the temporalities of the abbey of Lyre being in his hands on account of the war with France: on an exchange of benefices with Robert Sturmy. The like of Robert Sturmy to the said Church of Haversham in the King’s gift by reason of the keeping of the lands and heirs of Wm. de la Plaunk, tenant, being in his hands. LADY CLINTON, 1389 to 1423

Seal of Lady Clinton as appearing in a deed of 1416 Not for the first time in the story of Haversham has a lady of distinction been the central figure. Elizabeth de la Plaunche was born after the death of her father, Sir William, in 1347. In the sealed grants made to particular persons by the Sovereign, which are called “the Close Rolls,” she is twice referred to (in 1361 and 1372) as being co-heiress with her elder sister Katherine of the estates of their father. It would seem from these Rolls that some sort of a partition of the estates was made, or intended to be made, between them. As however Katherine died without children sometime after 1372 (exactly when is not known), the undivided ownership passed to Elizabeth, as the sole surviving child of Sir William de la Plaunche. Before she inherited her ancestral home and all its possessions, she had already come through marriage into the enjoyment of vast estates in many places; for instance there were manors and lands in Warwickshire (including Bermingham and Maxstoke Castle), in Staffordshire, Oxfordshire and other counties, as well as property on London and Southwark. She does not seem to have entered into full possession of the Haversham estates until 1389, when she was the second wife of John, the 3rd Lord Clinton, who had been prominent during the wars of Edward III and Richard II. Elizabeth, Lady Clinton is best known to history as collaborating with Walter Cook, Canon of Lincoln, in founding a Guild or College of ten priests at Knoll (or Knowle) in Warwickshire, of which foundation, it is said, she was “a great Benefactress.” The King’s licence for this project was obtained in 1416. At her death on Sept. 11th 1423, the line of the de la Plaunche came to an end, as the children of Lady Elizabeth had all pre-deceased her, and the manor passed to a collateral branch descended from the original family of the Havershams. At an inquisition held shortly afterwards at Wendover the jurors found that of the vast estates she had enjoyed in her lifetime, she held none in fee-tail but only for life, except a certain manor called Belney’s in Haversham.

The mystery of all these variations in spelling is solved by a statement in another series of ancient records, the Rolls of the Hundreds. There it was declared in 1278, on the evidence of 12 jurors, that John de Haversham held 90 acres of land from Baldwin de Belle Aneto, and that Baldwyn held it from Lady Matilda, the tenant in chief. It will be remembered that one of the earliest references which there are to the De Haversham family was in connection with the marriage of a daughter to William de Bello in 1174; and Bellou is a town in Normandy. In 1336 mention is made of a Richard de Belauney, deceased, who had held “a quarter of a knight’s fee” here: and six years later (1342) the property held formerly by Richard de Belauney was assigned in dower by the King to Hawisa, the widow of William de la Plaunche. From this time the name Belauney disappears from the list of the proprietors of this small manor, and on the next occasion when it is mentioned in the old records the information is given that in 1369, Walter de Miltecoumbe renounced whatever claim he might have had on “the fourth part of Haversham Manor” to Fulk de Birmingham. It was his son, John de Birmingham, who had married Elizabeth de la Plaunche of Haversham Manor eight years previously. This lady, better known as Lady Clinton, evidently had the small estate left her, through her father-in-law, for when she died in 1423 the jurors at the Inquisition found that, of all the vast estates she had enjoyed in her life-time, “a certain manor called Belney, in Haversham,” was the only portion which she was entitled to bequeath. She had settled it upon her last husband, Sir John Russell, and after him to his son John Russell, who was in Holy Orders. The value of this Manor House was then given at 10s and the whole estate, including 60 acres of arable land and 6 acres of meadow, was valued at 100s. In the Russell family this property remained for over a century. At his death in Midsummer 1502, Robert Russell is recorded as being in possession of a manor here worth 10 marks, and as being succeeded by his son John, aged 8 years. And again, John Russell, probably the same person, sold this manor to William Lucy, the Lord of the Manor of Haversham in 1533. From that time it appears to have been completely absorbed in the estate of the principal manor, and almost lost in obscurity. The situation of this small estate is evidently somewhere at the Hanslope end of the parish, in the neighbourhood of the old Pineham Farm. Close to this old house there is a field which is still called “Fulk’s Stockings” (i.e., stakings), possibly so called after Fulk de Birmingham, who once owned it. Its position, too, on the further side of the wood from Haversham Manor, agrees with the record of the joint gift of the bosky acres of Ernesdene to Lavendon Abbey in 1226. The present Pineham estate at the extreme north-west portion of the parish, consists of 104 acres, and is in the possession of Mr. Owen Goode. THE GRANGE A veil of mystery has long hung over the old building at the north end of the village, and least one strange story about it has been circulated, which has no foundation in fact. An attempt is here made to piece together what authentic information is available. Its story is connected with a certain parcel of land in the parish, which in the 13th, 15th and 16th centuries was called Ernesdene or Yernysden, and which had been given to the Abbey of Lavendon. Although no remains exist at Lavendon of this Abbey, it is known that John de Bidun built and endowed one there to the honour of St. Mary and St. John the Baptist about the end of the reign of Henry II, that is, before 1189, and that it consisted of 10 or 12 canons of the Premonstratenian order just before the dissolution of the monasteries. The first mention of Ernesdene does not happen to be in connection with the Abbey, but it is of help in locating its situation which is to the west of the parish and not far from the field called Lay Stockings. It will be remembered that this was one of the fields over which a test case was tried before King John in the year 1207. There are three fields known today as Arden Well, and evidently they cover the ground originally known as Ernesdene. In 1226 there is a record in connection with the “Abbatia de Lavindene” a gift of Nicholas de Haversham and Robert de Belauney to the Abbey of the whole wood of Ernesdene, and the land on which the wood is situated with what pertains to it (totum boscum de Ernesdene, et terram super qua boscus sedet cum pertinentiis). Thirty years later the Abbot of Lavendon obtained a licence to enclose the wood of Ernesden in the forest of Salcey with a dyke and hedge, to cut down the trees, and to cultivate the ground. The odd thing about this reference in Charter Rolls is that its location is said to be in Salcey Forest. Quite possibly this large forest, or detached portions of it, extended as far as the boundaries of Haversham parish seven centuries ago. “The steward of the forest on this side Trent,” at least, included this woodland within the Salcey forest area. It would seem that these lands are the 24 acres which Thomas de Britannia held in 1278 free of rental except a nominal one of 4d. and 1 pound of cumin, and 1d. to John de Haversham as well as 9 shillings “to God and the Church.” Another John de Haversham, who was a chaplain, obtained a licence in 1325 “for the alienation in mortmain (i.e., that it should belong to the Abbey for ever), to the Abbot and convent of Lavendon of 12 acres of land in Haversham in aid of the maintenance of a chaplain to celebrate divine service daily in the Church of the Abbey for the soul of the faithful departed. By fine of 20 shillings. This land would no doubt be in addition to Ernesdene and close to it. A hundred years pass over before any further reference to it can be found, and this time it is not so much a positive reference as a likely deduction. In her will of 1423 Lady Clinton requested that the seven priest, for whom she left a generous allowance for seven years, were to “have esement in the place called Hornes Place.” This place was evidently an appropriate establishment such as a religious settlement would provide. The field adjoining the Grange is today called Corner Close without any obvious reason. Two hundred years ago it was called Corn Close. May it not originally have been Hornes’ Close? There is a straight path or track leading from the Grange direct to the fields called Arden Wells, which is about ten minutes’ walk away. In a record of the rentals of William Lucy about 1476 it is said that the “Abbot of Lavendon held one Grange called Erenesden, and paid one pound of pepper to the Lord of the Manor annually at Christmas.” A previous account of the parish which has noted this reference in “Rentals and Surveys” has mistaken the initial letter E. for G, to which it is very similar in the original writing, but not identical, and so the word has been wrongly spelt Grenesden. At the dissolution of the monasteries about the year 1536, all religious houses and their property were valued, and among the lands possessed by the “Monasterium de Lavenden” are found these entries. Lathbury & Havereshame, annual value £13 15s 0d Yernysden, annual value 33s 4d. The land at Havereshame was no doubt the 12 acres given in 1325. Such are the historical references.

THE LUCY FAMILY, c.1457 to 1664

Arms: Grule Crusilly with 3 luces argent. At the inquisition held after the death of Lady Clinton, it was returned by the jurors that the next heir of the manor called “Plaunche’s Manor,” with the advowson of the Church, was William Lucy, who was “son of Alice, daughter of Margery, daughter of James, son of Joan, sister of William, father of William, father of the aforesaid Elizabeth.” The Matter however was not quite so simple as that, for a rival claimant appeared in the person of one who was descended from a second son of Maud de Haversham, although the third child. This person, Isobel de Olney, was a great-grand-daughter of the aggressive Sir John de Olney, and she had married Walter Strickland, Armiger. Her claim seems to have been upheld, for at her death in 1444 she was returned as being in possession of all the estates belonging to the old de Haversham family; namely, Haversham Manor, two parts of Cleybroke in Leicester, Compton Chamberleyn Manor and other lands in Wiltshire. Both Cleybroke and Compton Chamberleyn had come to be called “Lady Clynton” manors. These were inherited by her son Richard Strickland, a boy of 13 years, and it would seem that not until 1457 did the estates come into the undisputed possession of Sir William Lucy, the descendant of Joan, the daughter of Lady Maud.

Through the Lucy family held the Manor for over 200 years, they do not seem to have left their mark upon Haversham in any respect, except that they are mentioned ten times in the books of the Bishops of Lincoln as presenting to the benefice whenever a new rector was appointed. In this connection one of them is even described in 1572 as “Thomas Lucy of Harsham alias Haversham knt.” Apparently, they were hardly ever resident here; perhaps not at all. They are better known for their connection with Warwickshire, the home county of William Shakespeare, and in different ways they have left their mark on the pages of history. One of them, Edmund Lucy by name, was M.P. for the county of Warwick, and a soldier of high repute in the reign of Henry VII, commanding a division of the royal army at the battle of Stoke. On his succeeding to the estates of his father in 1491, it was officially put on record that he held the Manor of Haversham in the County of Buckingham (with the advowson) “worth £6 held of the king as of the honour of Peverel, by service of one knight’s fee,” as well as manors or lands in Gloucester, Salop and Bedford. His great-grandson, Sir Thomas Lucy, who inherited in 1551, is the one who was previously described as “of Harsham alias Haversham.” He was M.P. for Warwickshire and a Justice of the Peasce. He is world famous for being the prosecutor of William Shakespeare - of all people. The offence of the poet was that of poaching in the deer-park of Charlecote. It is a well known story, how some years later, the poet had his revenge, in his own amusing way, by making fun of him as “Justice Shallow” in “The Merry Wives of Windsor” “THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR,” Act I., Scene I.

Shallow, a Country Justice.

The poet represented “Slender” as mocking the pretensions of “Shallow” to distinguished ancestry by a definite allusion to his coat of arms (the luces) and “parson Evans” capped the jest by adding, “The dozen white louses do become an old coat well.” The Lucy family had certainly every right to be proud of their ancestry, but perhaps this gentleman allowed his pride to be a little too obvious. It is true that another candidate for this amusing honour has recently been put forward in a William Gardiner Sheriff of Surrey and Sussex, who bore in his coat of arms, by right of his wife, the three luces haurient argent of the Lucys. Sir Thomas Lucy died in 1600, and was succeeded by his son of the same name, whose six sons all took an active part in their country’s affairs, The eldest, also named Sir Thomas, succeeded in 1605, and was Member of Parliament for the county of Warwick in six successive parliaments. The youngest was also Member of Parliament for Warwick; another became Bishop of St. David’s: another was knighted; and the other two were either killed or died on service in France. Haversham Line of Lucy who held. Of Richard Lucy an old manuscript says that he “running much in debt and deeply mortgaging his demesnes here did in conjunction with one Currance the mortgagee a London Tailer, I am informed, Anno 1664, convey his estate to one Maurice Thompson.” The national rejoicings and the almost unbridled merriment which prevailed when the monarchy was restored in 1660 had evidently proved too great a temptation to Richard Lucy, and so Haversham was lost to the ancient family, in whose possession it had been for nearly 500 years, under the names of de Haversham, de la Plaunche, and Lucy.

THE THOMPSON FAMILY, 1664 – 1728

Maurice Thompson, who purchased the estate in 1664 , is rather rudely described in the old documents as being “a person of mean extraction.” At least, he had been a member of Cromwell’s government, as also his brother George had been, and he is said to have been an East India merchant. It was he who restored the ancient dovecote in 1665, and it was his wife Dorothy who repaired the Clinton monument in the same year, as an inscription on it testifies. Baron Haversham.

Arms: Or a fesse dancetty azure with 3 stars argent thereon And a quarter azure charged with a sun or. However “mean” their extraction might have been, the Thompson family soon made good, for John Thompson, who succeeded his father in 1671, had already become Sheriff of the County of Buckingham, and in 1673 was created a baronet. He inherited his father’s political and religious opinions and entered Parliament as a pronounced Whig. The Whig party was the champion of Parliamentary authority, while the Tories of those days supported rather the theory of the Divine right of the kings. It was in 1688, when the country had lost all patience with the Roman Catholic King James II, that a letter was sent to the two grandchildren of Charles I (William of Orange and his wife Mary) to come and deliver the country from “popery and slavery.” With the flight of James II to France on December 11th in that year, the “Divine right of kings” also disappeared. As a strong Protestant, Sir John Thompson was among the heartiest supporters of William and Mary, having been one of the first to sign the Invitation to the Prince of Orange to come to England. He was created Baron Haversham of Haversham in 1696, and three years later became Lord of the Admiralty. It was about this time that Lord Somers and other Whigs were attacked by the Tories because they had advised King William to agree to the treaty for the division of the Spanish monarchy. The Lower House, which was mostly Tory, demanded a joint committee to consider the impeachment of Somers. At this action of the Commons Lord Haversham was filled with indignation, and in vigorous language he accused them of partiality for attacking those who happened to be Whigs, while ignoring the fact that the Tories were equally responsible for the advice tendered to the King on this matter. The Commons, of course, resented his accusations but could do nothing more than make an ineffective protest, and so Somers was acquitted. In spite of this attack on the Tories, he joined their party in the days of “good Queen Anne,” when they too had become strong supporters of the Protestant succession, especially as the Whigs “drove at Schemes He could not down with,” Lord Haversham’s speeches. On several occasions his speeches in the House of Lords were of exceptional vigour, and often carried much weight. In a Memoir of him published in 1711, the year after his death, these speeches as written by himself were printed. This fact is noteworthy as being the first occasion on which the speeches of a member of the Upper House were so printed. Three times over the Commons passed a bill to prohibit this occasional conformity, and it was known to have the support of the Queen, and yet it never became law owing to the action of the Lords. For this tolerant attitude of the Upper House, perhaps the chief credit is due to the Lord of the Manor of Haversham, who wrote in his memoranda:- Although Sacheverell was found to be guilty, he was only given the nominal punishment of being suspended from preaching for three years and his sermon burnt by the common hangman. Lapse of the Title. His speech in defence of Sacheverell was the last which John Lord Haversham made in the House of Lords. After a short illness he died at Richmond on Nov. 1st, 1710, and was buried in the Church there. The bearers at his funeral were the Duke of Ormond, the Earl of Rochester, the Lords Hyde, Howard, Cheyney and Mohun. His first wife, Lady Annersley, a daughter of the Earl of Anglesey, died in 1704, and was buried in the vault under the Chapel floor at Haversham. Their son Maurice succeeded to the title as the 2nd Baron Haversham of Haversham. Unhappily, immediately on his succession to the title and estates, Lord Maurice lost both his wife, Lady Elizabeth, at the age of 32 years, and her infant child, Nothing seems to be recorded of him except that in 1728 he sold the Manor Estate to Lucy Knightly, Esq., for £24,500. When he died in 1745 his body was brought to Haversham Church to be interred, and with him the Barony became extinct. Manor House. It was Lord Haversham, or perhaps his father Maurice Thompson, who built the present Manor House. How long prior to this time a house had existed on this particular site there is some uncertainty. Originally it must surely have been enclosed by the moat, which is at a distance of about 140 yards away. The present house, at any rate, dates from the latter half of the 17th century, with possible traces of an older building. A considerable portion of it was taken down in 1792, and a new wing added bearing the initials “A.S., 1793 W.G.” (i.e. Alex Small & Wm Greaves.) The front portion of the Rectory House was added to the small original house about the time of Queen Anne. THE KNIGHTLEY FAMILY, 1728 – 1764

Arms:- Quarterly, 1st & 4th ermine, 2nd & 3rd paly of six, or and gules. All within a bordure azure. Mr. Lucy Knightley of Fawsley in Northamptonshire who acquired the Manor of Haversham in 1728, is described in a contemporary writing as “a gentleman of the very ancient gentle descent.” Ancient his descent certainly was, for his ancestor, Rainald de Knightley, came over with William the Conqueror, and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Several members of the Knightley family had taken a prominent part in the affairs of the country since the time of Henry VIII. In the reign of that monarch, Sir Edmund Knightley was one of the chief commissioners of the suppression of monasteries. In the days of Queen Mary, Sir Richard Knightley, Sheriff of the county of Northampton, was a champion of the Puritan party, and because he dared to sign a petition appealing against the suspension of the Puritan ministers in his county he was fined £10,000 by the Star Chamber and deprived of his position. His grandson, also named Richard Knightley, was closely allied with the well known patriot John Hampden, and it was his house at Fawsley that Hampden and others met in 1640 to decide upon a plan to control the king’s prerogative of making peace and war. The accounts of him, however, are careful to mention that Richard Knightley strongly disapproved of so extreme a measure as bringing King Charles to trial, and that he had no part in his execution. He was even imprisoned by the Parliamentary party in 1648 for opposing their action. His son, another Richard Knightley, sat in Richard Cromwell’s Parliament in 1658 and 1659 as a member for Northampton, and he was a member of the Council of State which recalled King Charles II, at whose coronation he was created K.B. The Lucy Knightley who acquired Haversham in 1728 was descended on his mother’s side from the Lucy family of Charlecote, and through them he could trace his connection with the de Haversham family of Norman times. In a sense, therefore when he purchased Haversham Manor from Maurice, Lord Haversham, he was bringing back an ancestral home into the possession of his family. Unfortunately, the Knightleys were not to retain possession for more than three generations. Mr. Lucy Knightley died in 1738 and was followed by his son Valentine, who was a Member of Parliament for Northants from 1748 until his death in 1754. His son, Lucy Knightley, who succeeded him, was also M.P. for Northants from 1763 to 1784. When this gentleman parted with Haversham after holding it for 10 years, the old family, which in a way, had been associated with this place for about 590 years (except for a break of 60 years), lost all connection with it for ever. Inclosure Act of 1764 The only respect in which the Knightley family seem to have left their mark upon Haversham is an account of an Act of Parliament, which was passed at the very end of their time. Being desirous “to inclose several open and common fields,” and to take over “certain Glebe lands belonging to the Rectory, which lie dispersed and intermixed with the lands of the said Lucy Kinghtley,” as well as to have vested in him “the Tithes now belonging to the Rectory or Parish Church of Haversham,” he had to obtain a special Act of Parliament to enable him to do so. As “compensation” he undertook to pay “one clear yearly Rent or Sum of £195 … to the Rectors of the said Parish Church of Haversham aforesaid for ever.” It seems somewhat strange that no sooner had Mr. Knightley got Parliamentary sanction to do this, than he sold his Haversham estate outright. It has already been noted that as early as 1278 it was recorded that the Church was endowed with 72 acres of land. In the Lincoln Record Office there is preserved a document of 1745, signed by the rector, John Mackerness, and the churchwardens, Thomas Line and Richard Wrenn, in which these lands are specified; and an amazing number of small parcels of land there were, all “dispersed and intermixed” with the manor property. Previous to the Act of 1764 the rectory possessed no cash endowments, but the rectors had to farm the land, which the church had held from ancient times. Public Roads.

These are the words by which they are defined:- “And be it further Enacted, that there shall at all Times be a publick Road of Forty Feet wide, from a certain Lane at the West End of the Town of Haversham aforesaid, leading towards Stoney Stratford, by the Seven Houses, and by the North side of an old Inclosure called the Pastures to the North-West corner of the said Pasture, and from thence over other Part of the said common Fields to the Town Meadow, and through and over the said Town Meadow to a certain Bridge called Mead Mill Bridge, across the River Ouze; and that there shall also be a publick Road Forty Feet wide leading out of the said Road at or near the North West corner of the said old Inclosures, along and over the common ground between the Brook Field and Middle Field to a Slade called Royal Slade, across the Royal Slade over Sand Pit Hill, and over Stone Bridge Hill to a certain Ford called Long Ford; a Road Forty Feet wide from a certain Lane leading out of the ancient Inclosures of Haversham, at or near a certain Close called Stonepit Close, along the Ridgeway, to the Parish and Manor of Haversham aforesaid, called the Stocking Closes, from thence by the South Side of the said Stocking Closes and a certain Wood or Coppice called the Grove, to the South West corner of the same, and from thence over a certain Furlong called Grove Furlong, to a certain Ford called Short Ford, dividing the Parishes of Hanslope and Haversham.; a Road Forty feet wide from and out of the past mentioned Road at or near the South West Corner of the Grove Furlong by the East Side of the Short Ford Furlong, and by the East Side of the Two certain Closes called Herbert’s Close and Bushy’s Close, into the past mentioned Road leading to Long Ford, at or near the Top of Stone Bridge Hill; a Road Forty Feet wide from the North East End of the Town of Haversham aforesaid, by the North Side of a certain old Inclosure called the Corn Close, to a certain Lane leading into or through other old Inclosures, at a gate near the South West Corner of a Close called Stonepit Close; as the same are now staked out.” GREAVES FAMILY 1815 - 1919

Quarterly gules and vert an eagle holding in his beak a slip of oak all or 1764 – 1937 Division of the Manor Estate. In the year that the Inclosure Act was passed, the Manor, Parish and Advowson were purchased by the trustees of Alexander Small, he being at the time a minor. Mr. Small also possessed the Manors of Hardmead and Clifton Reynes, at which latter place he resided. In a contemporary paper he is described as “a great sportsman.” It is also said of him that his general conduct was such “as to occasion great uneasiness at home.” He and his son of the same name held Haversham for 42 years, without adding much distinction to it. On the death of the second Alexander Small in 1806, the Trustees, acting on behalf of the infant heir, sold the manor estate, but retained the advowson of the Church for the benefit of the young child, so that he might become the rector himself when old enough. The estate, or 923 acres if it, was acquired by the two churchwardens of the time, William Greaves and Roger Ratcliffe. They and their fathers before them had held office as churchwardens for the previous forty years. After these two gentlemen had jointly held the estate for nine years, an arrangement was made in 1815 by which the Manor portion of 563 acres was assigned to Mr. Greaves for £15,000, and the Mill portion of 360 acres to Mr. Ratcliffe for £6,000. On the death of Wm. Greaves two years later a further division of the Manor property was made, Field Farm being carved out of it, and the reduced Manor portion became vested in his brother, Thomas Greaves, while Field Farm went to the younger brother James. The whole area in which the later farmed is situated was known in the 18th century as the Brook Field, to distinguish it from the Middle Field on the other side of the Slade Way, and the Wood Field beyond the Ridge Way. Thomas Greaves was succeeded in the ownership of the Manor by his son Edmund in 1826, who held it until 1867, when it came to a nephew of the latter, the Rev. John Albert Greaves, Vicar of Towcester, and afterwards Rector of Great Leighs in Essex. The Greaves family finally parted with the estate in 1919, and since that time four different families have been in possession. By Peter North Mr. Shaw In 1921 the owner of Haversham Manor was a Mr Shaw who came here from Newbury, in June of that year the whole of the estate at Stowe near Buckingham was to be sold by auction. The sale was catalogued to last 3 days, the whole estate to be offered in one lot but if it did not reach the reserve price to be sold in small lots. Mr Shaw who had very little money, went to the auctioneers Jackson Stops and Staff of Northampton to try to buy it they told him "if you come with the money you can have it at the reserve price", he then asked his friends and neighbouring farmers to lend him the money, but he could not raise enough funds. Mr Shaw then went to all the tenant farmers on the Stowe Estate to find out which were interested in buying their own farms and how much they were prepared to pay. He then went to the sale and bought the whole estate at the reserve price, then said to the auctioneer "now sell as per the catalogue". The first day’s sale came to the amount he had paid for the whole estate, the next two days sale was all profit for him as all the advertising had been done and all the catalogues printed, all the prospective buyers were there. Included in the sale were a set of seven statues; one representing each day of the week with the name of the day engraved in Latin:they were sold at the sale for between £12 and £14 each. In an article in the Buckingham Advertiser in the early 1990s it said a museum had found six of them for which they had paid between £46,000 and £60,000 each but they could not find the one representing Sunday and asked 'do you know who bought Sunday?' Extracts from: "The Story of Haversham" by Rev. Samuel Hilton, M.A. Rector of Haversham Growth of Population. In the year of Queen Victoria’s accession another matter of national importance happened, destined to transform completely the character of the parish and neighbourhood, which had hitherto been purely of an agricultural nature.

It was in 1837 that the first part of the “London to Birmingham Railway” was opened, known later as the L.N.W. Railway, and more recently as the L.M.S. Railway.

Not only did over half a mile of this railway pass through the south-west corner of the parish, including the well-known viaduct, but just over the parish borders one of the chief carriage works in connection with this railway system was soon to be established, and to attract to this part of the county a large and entirely new population. Strange to say, the population within the parish of Haversham did not at first show signs of increasing as a consequence, but rather the reverse. In 1831 the number of inhabitants was returned at 313, with 54 houses. In 1861 it was 280; by 1891 it had gone down to 224; and at the last census in 1931 the number had sunk to the low figure of 164, with 46 inhabited houses, a population not much more than it was when the first official returns were made in 1086! Since the last census, a great transformation has taken place by the conversion of fields near the Wolverton border into building estates, and in the past three years the population has trebled and is still increasing. May the new parishioners of “Haversham Green” come to value the inheritance which they now share with the original village, in a parish rich in its historical associations, and in a Church which is one of the nation’s cherished treasures. The Story of Haversham by S. Hilton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||